Are you a tinkerer?

Tinkering, to most people, implies ‘messing about’ or playing with something: taking physical things apart, or making them, and not always with a set goal in mind. I don’t consider myself a tinkerer, but becoming a parent in an innovation hub such as Boston has made me take a closer look at creative ways of learning (particularly in light of my own traditional schooling in India). While growing up, I watched my brother (six years my senior and a master tinkerer) constantly engage in what we now recognize as ‘hands-on learning’, in stark contrast to the rote memorization rewarded at our school. His preferred form of play involved taking perfectly functional household gadgets apart to find out how they worked. To the shock of my parents and extended family, the reassembled gadgets always worked as well (or better) than before. In one notorious instance of ‘improvement’, he fiddled with a speaker system installed throughout the house until it could also act as a microphone, allowing him to listen in on all rooms secretly. His ten-year-old self wasn’t appreciated as the ‘gifted and talented’ child he clearly was until much later.

But not everyone is interested in playing with gadgets, or mechanically inclined from an early age. I certainly wasn’t. I just didn’t have the same passion for gadgets that my brother did, and even less interest in opening them up. I gravitated to books for my leisure and learning, which made me a great fit for traditional schools and also later for graduate school in molecular biology. My brother’s childhood obsession with stereos and TVs, combined with his love of music, eventually led him to a successful career as a sound engineer and entrepreneur. He now runs a music production company while training the next generation of sound engineers at a training institute he founded. Looking back, his tinkering habits make sense in the context of his generally risk-taking (fearless), curious nature, coupled with his indifference to other people’s opinions. My ‘good girl’ habits included pleasing teachers and parents with great grades and staying out of trouble!

Why we should all try tinkering

So tinkering is not for everyone, right? As a more abstract learner myself, I couldn’t agree more. But I do think there is a huge value in exposing all children to hands-on tinkering (particularly girls, who are less frequently drawn to gadgets). Even an abstract learner, like myself, can benefit from the mindset shift that tinkering can bring–becoming more comfortable with risk-taking, hands-on action-led exploration can help us be more flexible, creative and, ultimately, innovative.

Much has been written about the usefulness of design thinking in education, but the more playful, less directed, tinkering approach is worth considering as a complementary learning tool in the classroom and the home. Whereas design thinking (a process that emerged from product design, popularized by IDEO and Stanford’s d.school) is a wonderful tool for problem-solving, tinkering is more open-ended (usually inspired by curiosity, not solution-seeking). Importantly, tinkering also involves taking the time to explore materials to develop familiarity with (or mastery of) the chosen tools and materials and is not typically constrained by a deadline or customer.

Some define unstructured or ‘aimless’ exploration as an ‘early stage’ of tinkering, in contrast to more goal-driven ‘late stage’ tinkering; however, it is important (particularly when working with children) to allow enough time for this open-ended exploration of chosen materials. A project or creative idea may only emerge after sufficient familiarity with a medium, and to always work with a goal-oriented, ‘top-down’ planning mindset can be limiting. On the other hand, as MIT Media Lab’s Mitch Resnick and Eric Rosenbaum describe in “Designing for Tinkerability” [1], tinkering does not end there. Random exploration is not true tinkering either; rather, true tinkerers know how to turn their initial exploration of materials into focused goal-oriented activity, which is what makes tinkering such a valuable process. Expert practitioners of STEM disciplines tinker much more in their work than classrooms allow, highlighting the validity of tinkering as a way of learning and organizing work.

Developing the tinkering habit can also allow children to preserve the element of playfulness they tend to lose as they get older and less engaged in hands-on, open-ended play. Our children lead highly structured and time-constrained lives (and the problem worsens as they get older). Thus, it is important for them to have time for free play. Even in cases where ‘unstructured’ tinkering doesn’t lead to a defined project, it has considerable value because things learned through this playful exploration can be used for future projects and ideas.

Finally, while it is more immediately apparent how tinkering can play an important role in disciplines that involve hands-on learning (such as science or engineering), the mindset behind tinkering can also be applied to less hands-on, more abstract subjects (such as writing a story or tinkering with ideas). As parents and educators, we can support our learners better if we acknowledge tinkering as a distinct (non-inferior) mode of learning and of organizing work, a viable alternative to top-down planning.

Given the constraints that schools face, it is up to us parents to provide a home environment that encourages experimentation and offers opportunities for playing with real tools, gadgets, and materials, not just toys. So, tinkerer or not — I hope these ideas inspire us all to get our hands dirty and try tinkering — for our kids’ sake and our own!

Tinkering 101

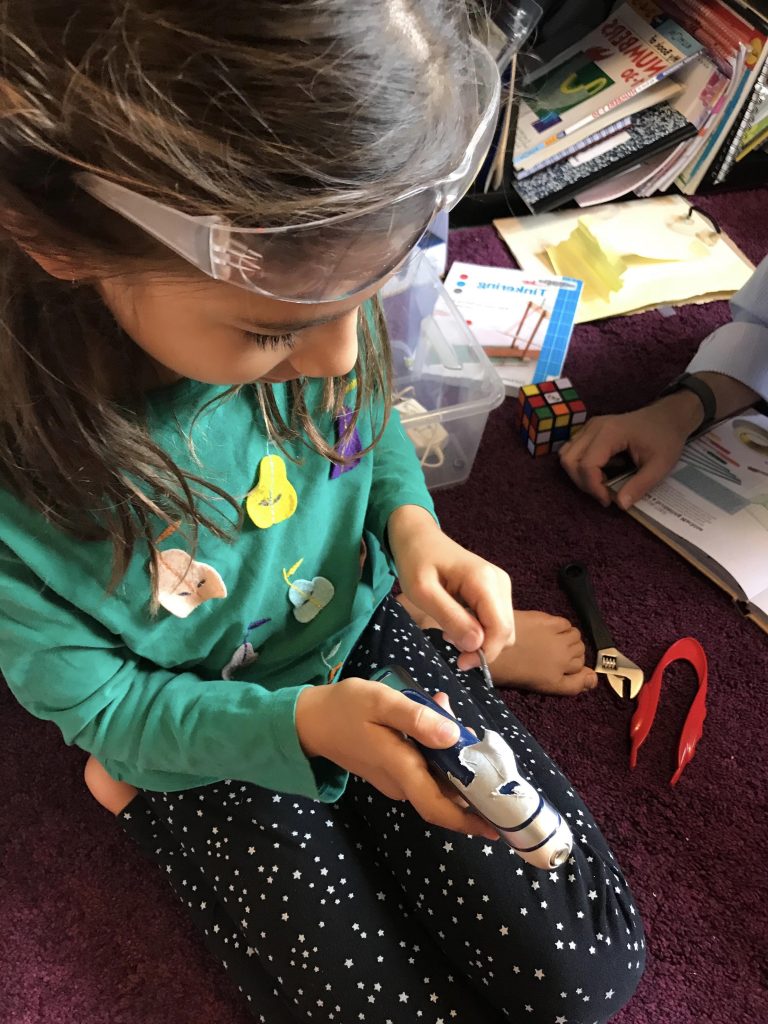

Being a non-tinkerer myself, I decided to ease myself into it by trying two simple, yet classic tinkering activities with my kids (aged 5 and 7). First, we took apart an old electric toothbrush with their toolkits (we love the cheap ones from IKEA and have one for each kid). I was surprised that the kids could roughly guess the purpose of the main parts (motor, gear, charging coil, etc.). We spent some time playing with the parts and thinking about other possible uses for them in other projects. Next, we set up a tinkering box to store the dismantled bits and bobs for reusing later. The only piece I suggested discarding was the toothbrush’s handle because its outer rubbery plastic coating had started to degrade. Our daughter, however, kept playing with it and ended up scraping off all the ruined material and saving the (now clean) handle “for more tinkering later”. Lesson learned!

For the second activity, we turned to the Art of Tinkering [2] (a wonderful source of inspiration), and the kids chose a well-known beginner project: making a scribbling machine from everyday objects. The machine is a simple contraption with a holder for pens, designed to draw by moving independently with the help of a motor. Complete instructions can easily be found online from a variety of sources; we basically attached small markers to a plastic fruit container, and then added a battery-operated motor with a weight to make it move. We repurposed a small metal bar from the dismantled toothbrush as a weight to attach to the motor, and experimented with substituting different objects for the various components.

The kids loved these two playful activities; the tech aspect (albeit fairly low), was different enough from their usual play to generate extra excitement. It’s a small start (and following a project idea from a book doesn’t fit the classic definition of tinkering), but I hope these explorations set the stage for more tinkering experiments in the future.

A few tips to encourage the tinkering habit and mindset (adapted from The Art of Tinkering [2], a fantastic resource from the directors of the Tinkering Studio at San Francisco’s Exploratorium):

Be open to combining science, art, and technology

- Play around with familiar household materials (pantry items, toothpicks, tape, toilet paper rolls, other recyclables) – and try to use them in new ways

- Get comfortable with your tools (whether it’s knitting needles or fancy circuits, fluency with tools helps)

- Prototype rapidly (begin sketching designs or building models right away), reflect and iterate

- Try to avoid thinking there is one perfect solution for any problem

- Have fun! (If it’s not playful, it’s not tinkering

*activities adapted from The Art of Tinkering [2], a fantastic resource from the directors of the Tinkering Studio at San Francisco’s Exploratorium

References:

- [1] Resnick, M., and Rosenbaum, E. (2013). Designing for Tinkerability. In Honey, M., & Kanter, D. (eds.), Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators, pp. 163-181. Routledge, New York.

- [2] Doorley, R. (2014). Tinker Lab: A Hands-on Guide for Little Inventors. Roost Books, Boston.

- [3] Wilkinson, K., and Petrich, M. (2014). The art of tinkering. Weldon Owen, San Francisco.

- [4] Bevan, B., Petrich, M., and Wilkinson, K. (2014) Tinkering is Serious Play. Educational Leadership, vol. 72, no. 4, “STEM for all”, pp. 28-33.